The twin shocks of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent global inflationary spiral have left the global economy on the precipice of recession. While the United States, the UK and the EU focus on the domestic implications of these global headwinds, developing countries in Africa, South-East Asia, Central Asia and Central America are faced with dire economic problems and an urgent need for development assistance.

The latest UN Development Report found that its human development index (HDI) has fallen for two consecutive years for the first time ever. The risk to developing countries of another lost decade is palpable.

In times past, foreign aid has supplied funds to support developing countries in situations of need, as well as provide investment to help foster the opportunities for growth. For instance, aid has helped fund education, health and infrastructure programs. As well as tempered the impact of conflict and the spread of infectious diseases, such as HIV and malaria. Moreover, aid was not only a financial phenomenon, primarily the concern of opaque funding institutions and central governments, but also a cultural phenomenon, supported by voters on both sides of the political spectrum. Most people can recall the Live 8 concerts of the mid-2000s. Hundreds of artists performed in those concerts to a global audience of of millions. Aid was big, it was relevant, and it mattered.

This momentum culminated in several pledges to increase global aid donations. The European Union committed to donating 0.7% of GNI every year by 2015. President Bush announced that the United States will double assistance to Africa between 2004 and 2010. And, under the Blair and Brown Labour governments, the former Department for International Development (DFID) grew into one of the worlds leading aid institutions. Of course, many pledges were not kept and criticisms of non-action and false promises were and have been made. However, clearly aid was high on the political agenda, and more importantly it was making a tangible difference.

But the 2000s are ancient history. Where are we right now? I focus on the UK here as I know more about the country.

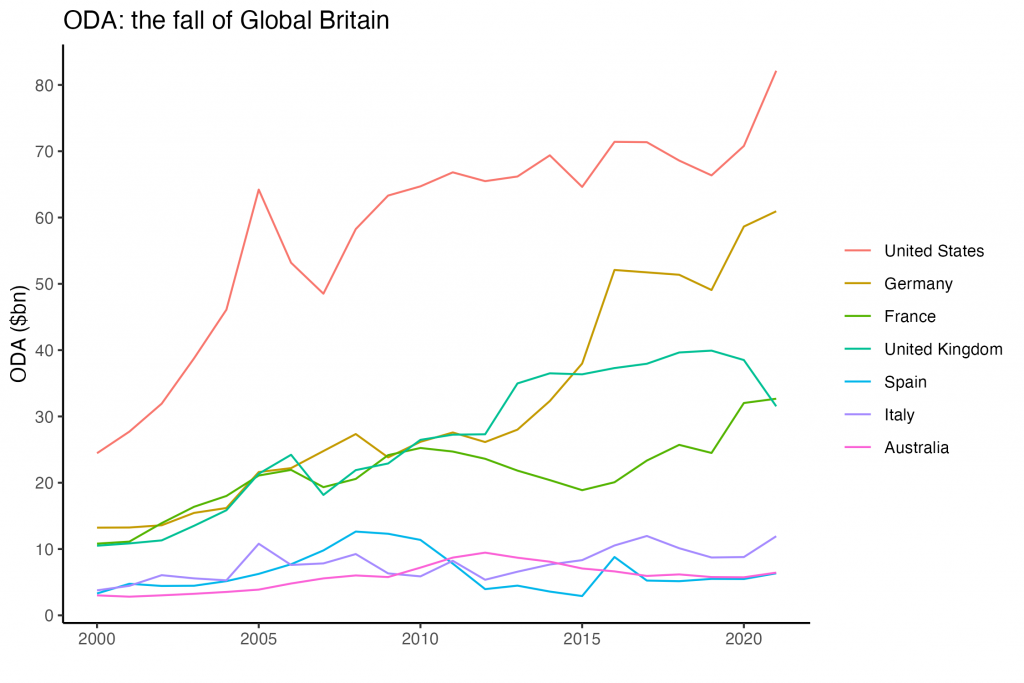

The last decade was an extremely difficult period for UK aid, which ended in the dissolution of DFID, cuts to the aid budget, and open remarks by leading politicians criticising the very purpose of aid. In fact, today, aid barely gets a mention in public discourse. This point was brought up in the excellent “The Rest is Politics” podcast with Alistair Campbell and Rory Stewart (Oct 18th). They mention the UK is committing a fraction of what it formally would have done and many countries are the verge of crisis. The bottom line is nobody in Westminster is talking about Africa right now and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office appears to be a vacuum of leadership on the issue.

Source: ODA DAC1 Flows, my own analysis.

Yet, there may be a faint glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. Kier Starmer has recently publicly committed to re-forming DFID and restoring the UK 0.7% commitment target on foreign aid, which was reduced to 0.5% by the Conservatives. This would be a very welcome improvement and a positive step. But, given the disastrous past few weeks in the gilt markets, any Labour government that comes into power, whether that be this year, next, or in 2025, may find its hands increasingly tied when it comes to spending. Also, the dark tunnel we are currently in may get darker still; this week there have been rumblings reported of a further cut to the aid budget down to 0.3%.

Regardless of what happens in the coming weeks in British politics it’s highly unlikely the new PM will make it his or her priority to reinstate the UK as a global leader in foreign aid. The promise of a “Global Britain” post-Brexit has failed spectacularly on so many fronts, just take the US trade deal for example, but in the sphere of development our fall from grace couldn’t be larger.