“You see the problem those British and French made, and then left for us to solve?” Salifu would ask my brothers and me. “What happens when your house is divided?”

Excerpt from My First Coup D’Etat, an auto-biographical account of post-independence Ghana by John Mahama, former President of Ghana.

What happens when your house is divided? Such a conundrum faced members of the Ewe tribe, whose homeland straddles the contemporary national borders of Ghana and Togo. Journeying to work in the morning, families belonging to the Ewe walk out of their front door into Ghana, but, when they return home in the evening, relax in their backyards in Togo. A confusing reality, which leads many people to question exactly who they are, and where they belong. Across Africa it’s estimated that a third of historical homelands belong to two or more present day countries; with 30-40% of Africans belonging to these partitioned groups. Africa also has the largest share of landlocked countries, fencing in millions of people from the benefits of international trade, and exposing them to the vicissitudes and bad policies of neighbouring countries.

Landlockedness and ethnolinguitistic fractionalisation are a consequence of artificial border design following the Scramble for Africa (1885-1914), a period of European discovery and partitioning of African societies and land. The historical legacy of the Scramble can be seen today: strong statistical evidence shows that contemporary conflict, weak governance, and low development can be attributed to the arbitrary boundaries drawn by the European powers (for an excellent review of the latest evidence see this paper).

A vast area of Africa, plagued by the historical consequences of European division and colonial administration, is the Sahel. The Sahel is a semi-arid stretch of land, enclosed to the north by the Sahara Desert, and to the south by the savannahs. The name ‘Sahel’ is an Arabic word for coast, referring to the boundaries of the region between the Atlantic coast of West Africa and the Red Sea in the east. Several states belong to the Sahel, including Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Nigeria, and Sudan.

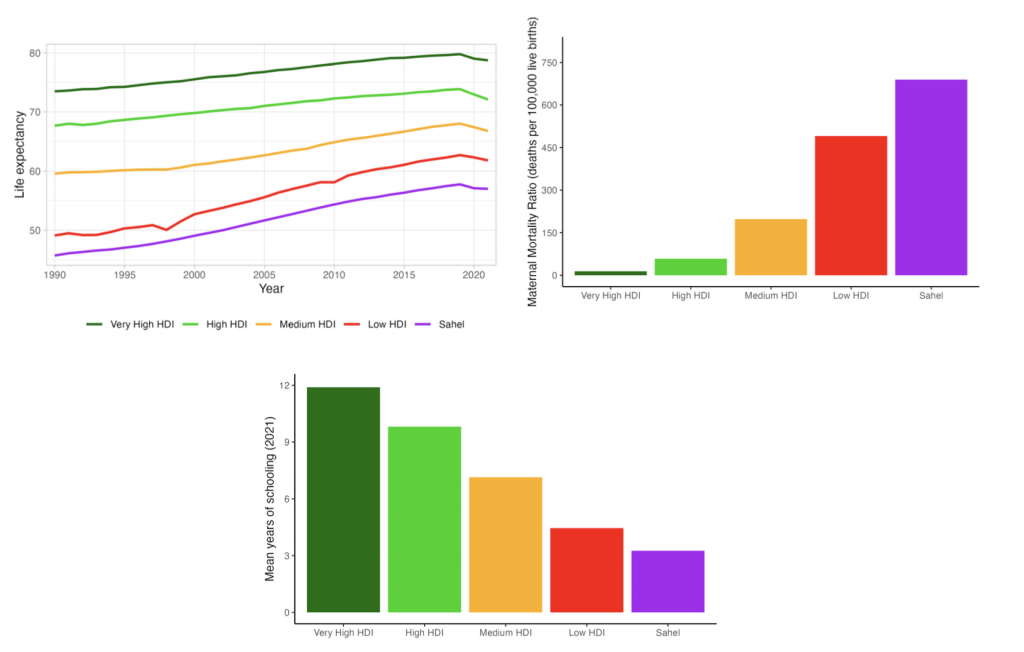

Sahelian states are amongst the poorest and least developed countries in the world. For example, the UN estimates 10 million children are in need of humanitarian assistance in the Sahel. Figure 1 compares the Sahel to other countries in the world, categorised by their Human Development Index (HDI). HDI is a measure which takes into account health, education, and income to assess the overall development of a country. Despite noticeable improvements in the past 30 years, life expectancy in the Sahel remains 20 years less than very high HDI countries and 4 years less than low HDI countries. Maternal mortality (i.e number of maternal deaths per 100k live births) is very high in the Sahel – approximately 3.5 times that of medium HDI countries, and 50 times that of very high HDI countries. Educational attainment is also extremely weak, the average years spent in school being only three. This issue is particular acute for young women – in some regions of the Sahel up to 80% of young women were married as children, and 95% of child brides don’t receive any education.

The Sahel’s poor development reflects the regions persistent struggles against several overlapping crises. For example, the climate crisis is aggravating the already naturally extreme climate conditions in the Sahel: drought and desertification being two of the most common threats. Security is also a major concern in the area. For instance, the Global Terrorism Index 2023 finds that the Sahel region is now the centre of global terrorist activity, accounting for more deaths due to terrorism in 2022 than South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa combined. A 2,000% increase since 2011. As the military juntas now in control of Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and other Sahelian countries focus on consolidating power in their capitals, state authority in the countryside has been diminished further, leaving power vacuums for terrorist groups already active in the area.

As mentioned above, the imposition of state boundaries along mostly unknown territory, with little regard to local conditions, was particularly damaging to the Sahel region. The Sahel has been a home to nomadic peoples for centuries, a way of life that necessitates free movement across a wide area. Borders created states of various shapes and sizes, containing several ethnic groups, languages, and cultural practises. Further, colonial institutions favoured different groups through indirect rule, pitting them against each other, and creating historical grievances between peoples. The historical legacy of these events exacerbates the proximate causes of crisis, such as climate change and terrorism, by limiting the power of the state.

A case in point is the Tuareg of northern Mali. A group who once saw themselves as the ‘masters of the desert’, found themselves a tiny minority within the new borders of Mali, ruled by the predominantly black population in the south. Consequently, the state making process in Mali has been extremely fractured because of the disconnect between the people and the state authority. This socioeconomic and political exclusion then manifests into violence.

Issues with internal security and underdevelopment in the Sahel are unique due their state and non-state aspects. As such, a UN report from 2016 characterises the region as a regional security complex. A regional security complex is a collection of states whose interconnectedness in relation to security necessitates the unit of analysis to be at the region level, as opposed to along state lines. This classification speaks to the arbitrary nature of the state boundaries in the Sahel created through the Scramble for Africa. Many of the underlying security and developmental challenges have their root cause in the structural configuration of the Sahel itself. Hence, any solutions will need to be built on trans-national policies, which recognise the unique qualities of life in the Sahel.

The West shouldn’t and cannot ignore the problems in the Sahel. So much of the ongoing crises are rooted in Western interventions, not least the Scramble for Africa, without even mentioning the transatlantic slave trade (which I will write about in a follow up post). Yet, the world’s focus is not on Africa. France has left West Africa following the Niger coup, the UK has massively diminished its role in terms of ODA (Official Development Assistance; aid), and America is spread thin responding to wars in Ukraine and Gaza, as well as precariously balancing relations with China. However, ignoring the Sahel threatens the continued spread of terrorism and will inflame the migrant crisis in Europe – both important issues for voters. Regardless of that, 10 million children in need of humanitarian assistance should be a strong enough case to grab the attention of the EU, America, and the rest of the world. Of course, African leaders and peoples will need to take the charge on this issue, but without external support, delivered with an appreciation of the unique context regarding the Sahel, the challenges will be insurmountable for decades to come.