One of my favourite books last year was “Doughnut Economics” by Kate Raworth. In it she outlined how the economics profession needed to adapt and grow to the challenges of the 21st century. Specifically, she argued that a new model was required; one which could both deliver the economic necessities for the global poor without destroying the very source of all wealth – the environment. Amusingly, this meant we had to reach that sweet spot of a ringed doughnut.

Chapter 7 of the book was particularly interesting as it brought forward an argument which is rarely talked about in the mainstream – being antagonistic about the pursuit of economic growth.

A number of questions arise. Is growth a political necessity? Is it desirable? And perhaps most importantly is it achievable within planetary boundaries?

Let’s, for now, accept that growth is both necessary and desirable in the 21st century (obvious for low-income developing countries but contestable in advanced countries). Then, how can we achieve growth without harming the environment? The answer is a process of de-coupling between GDP and emissions – sort of like an economic version of Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin.

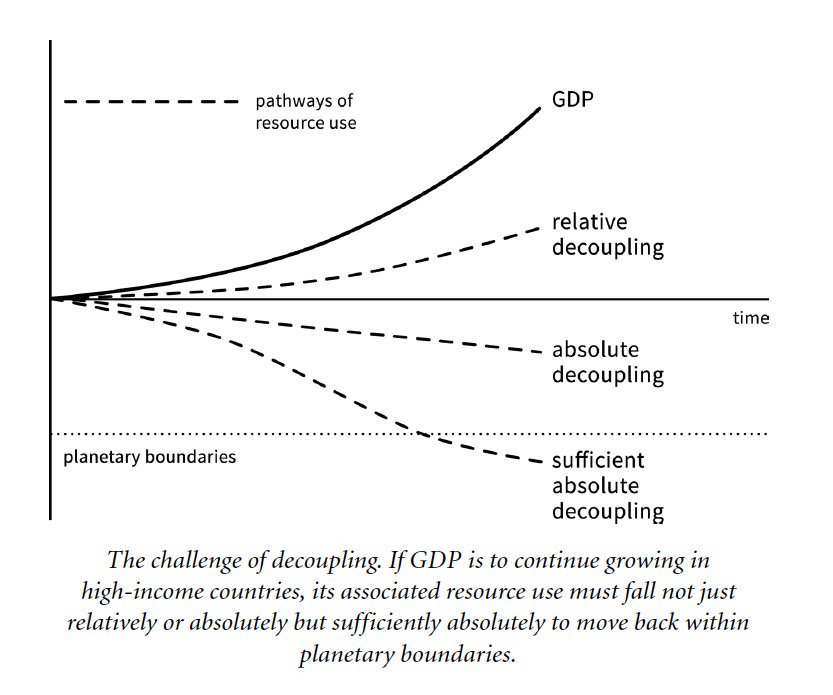

The above diagram shows the process of de-coupling occurring. For most of the previous 100-150 years growth has been closely followed by emissions. A reversal of this is required in the 21st century if we hope to curtail the degradation of the environment. This is shown by the divergence between the pathways of resource use and GDP growth across time. For example, if from 2019-2022 GDP grew at 3% and emissions grew at 1% then relative de-coupling would have occurred.

So how are things looking?

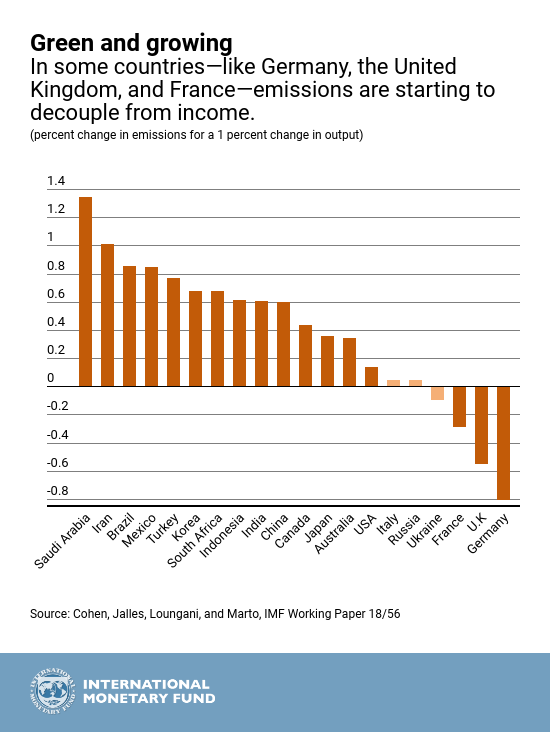

A paper last year by IMF economists (see source) found some promising results for the advanced economies of Germany, UK, and France. Their analysis found statistically significant evidence of absolute de-coupling between output growth and emissions growth. However, for many of the other economies only relative de-coupling had been achieved. Nevertheless, it’s encouraging that the UK, France, and Germany have implemented policies to transition away from fossil fuels and these seem to have worked – proving that taking coordinated action can achieve results.

Yet, relative de-coupling – while a step in the right direction – may not be enough to achieve the climate goals outlined in the Paris climate agreement. Unfortunately, it appears that many economies are still at this stage. Moreover, sufficient absolute de-coupling is required and we don’t know whether that would require an elasticity between output growth and emissions of -0.5 or -0.9 or even -1.3.

De-coupling does then seem to be possible. But maybe only for the wealthy vegan pop-stars among us.