Trickledown economics is back with a vengeance this week, as Kwasi Kwarteng, the new Etonian and Harvard educated Chancellor, announced his so called “mini” budget today. The labor front-bench derided his bonfire of tax cuts as a return to trickledown, quoting President Biden, who tweeted earlier this week:

Kwarteng’s response in the commons: “For too long in this country, we have indulged in a fight over redistribution. Now, we need to focus on growth”. Nobody in economic policy is against growth. However, achieving growth by cutting the top rate of income tax and scrapping the cap on bankers bonuses – now that is a lot more contentious.

Trickledown, at its core, is entirely based on the idea of incentives. In the new governments view, taxes reduce incentives for wealth creation because they reduce the amount of money available in the pockets of people who are the most innovative, hard working, and industrious. By lowering the burden of tax on these people, the hope is that they will spur new spending, investment, and generally start working harder and better. As a consequence, the riding tide will lift all boats and we will all be better off through more and better paid jobs. In fact, Truss and her allies will hope that the tide will rise so much that these tax cuts will pay for themselves through growth.

In theory, it’s not entirely implausible that by removing burdensome taxes the economy can be kickstarted. However, trickledown isn’t really about tax reform, or reducing taxes where they are most harmful to growth. It’s a pure and simple handout to the already extremely wealthy and rich members of societies with the blind hope it will somehow benefit the rest. Kwasi may loath policy makers focus on redistribution, but he’s certainly not afraid to redistribute to the very top of society.

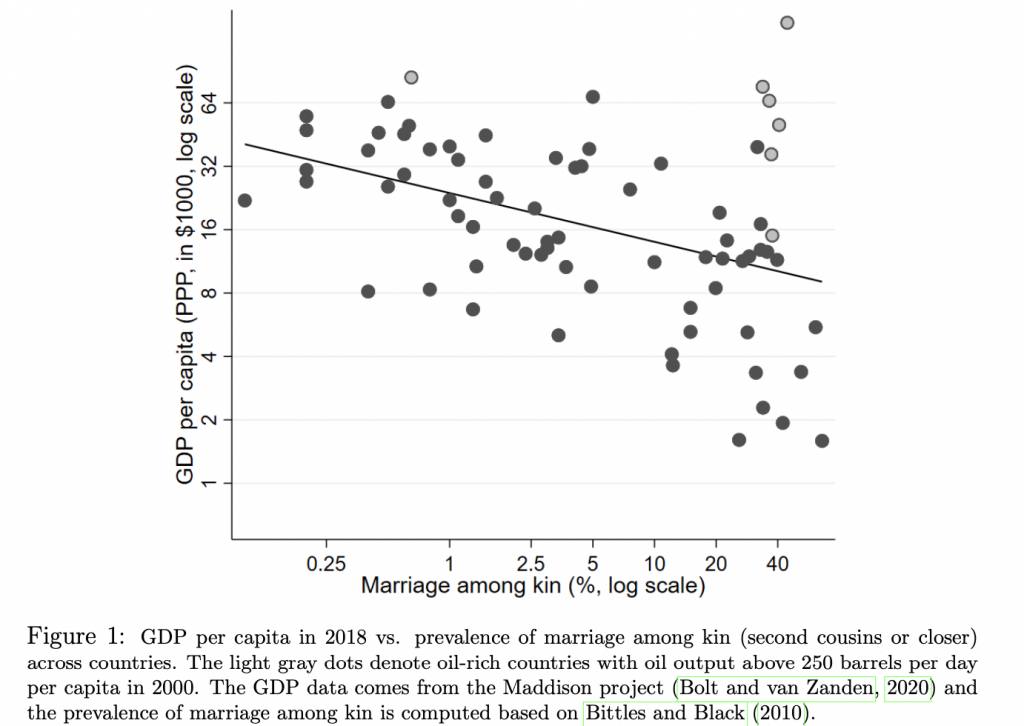

Trickledown is not a new idea, but fortunately that means it’s been tried before, and people have analysed whether it works. So what does the evidence say? An IMF paper published in 2015 found that increasing the top 20%’s share of income was actually bad for growth in the medium term. This is driven by the fact that, among other things, a widening gap between the rich and poor creates political instability, lowers investment in education, and increases the probability of financial crisis.

In another paper, published by the LSE International Inequalities Institute in December 2020, researchers find that tax cuts on the rich have no effect on economic growth. Their main finding is that, overall cutting taxes on the rich has no effect on growth and only leads to more inequality.

Overall, our analysis finds strong evidence that cutting taxes on the rich increases income inequality but has no effect on growth or unemployment.

The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich, LSE 2020

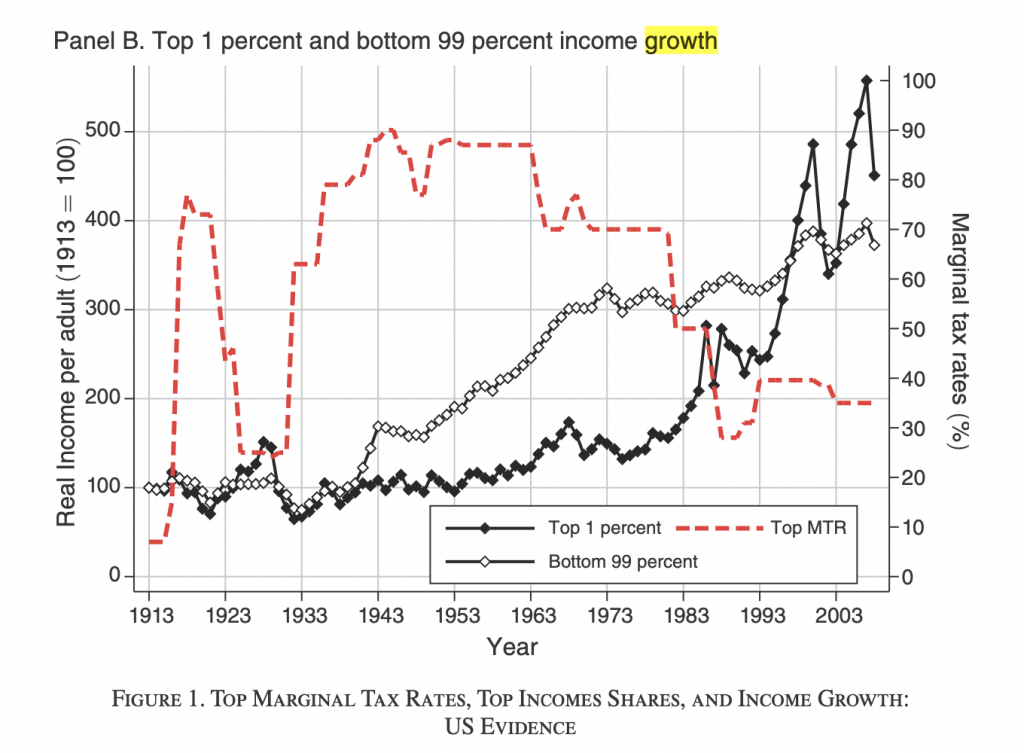

In another paper, Picketty and co authors run a series of models and also find no connection between the rate of tax on top earners and the growth of GDP. A really revealing graph from that paper is shown below. This is for the United States but the story is very similar for the UK.

It shows you how from 1950 to around 1970 the real incomes of the worst off in society grew exponentially quickly. This is the what economic historians call the “golden age of growth”. By many accounts, this was the largest sustained increase in living standard in history. What is telling is the red-line. During this period of miraculous growth the top marginal tax rate (i.e the tax rate paid on an additional dollar earned by the highest incomes) never fell below roughly 70%. Today it was announced that the 45% rate on earnings over £150,000 will be scrapped and the highest rate will be now 40% for incomes over £50,000. It appears the he chancellor, who by the way hold a PhD in Economic History from Cambridge, will do well to actually study the history of growth. During the time where the economy grew the fastest the top rate of tax was way above what it is today.

The government is taking a huge gamble on a policy that is proven to not work. The only affect this will have is to drive up inequality and increase division in an already divided society. The fate of the UK economy appears to be on a knife edge, or as Kwarteng call it today, a “new era”. But nothing has changed, the Conservatives have slipped their mask and revealed their fundamental support for the wealthy and privileged few. All of this under the pretence of an intellectually flawed and empirically unsupported fantasy. The next few months will be interesting.