At the group stages of the Qatar World Cup draw to a close, the growing excitement of the football has dissipated some of the earlier anger at the event being hosted in a country with multiple human rights abuses and a very poor record on migrant worker treatment. Rightly these issues deserve serious attention, but it’s not obvious what the ethics are of who is able to host world sporting events and who isn’t. Nonetheless, if places like Qatar are going to host sporting occasions in the future it’s only right to scrutinise and understand the nature of the problems within those countries, just as we should our own. Hence, I hope to shed some light on the makeup of economic inequality in Qatar – which is inherently related to the conditions and pay of migrant workers.

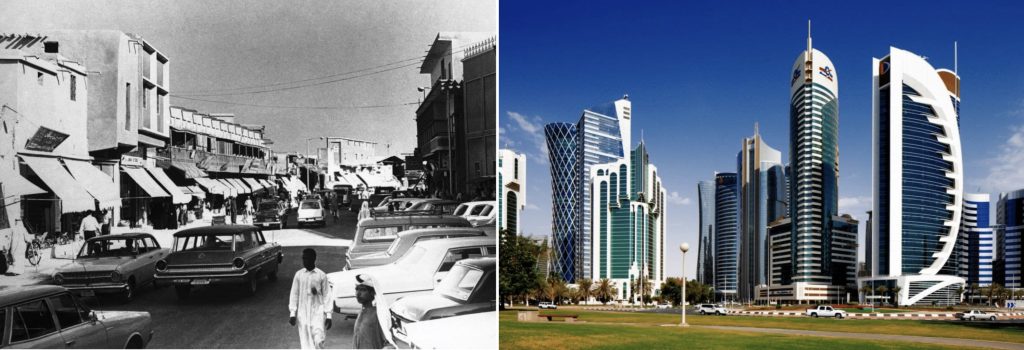

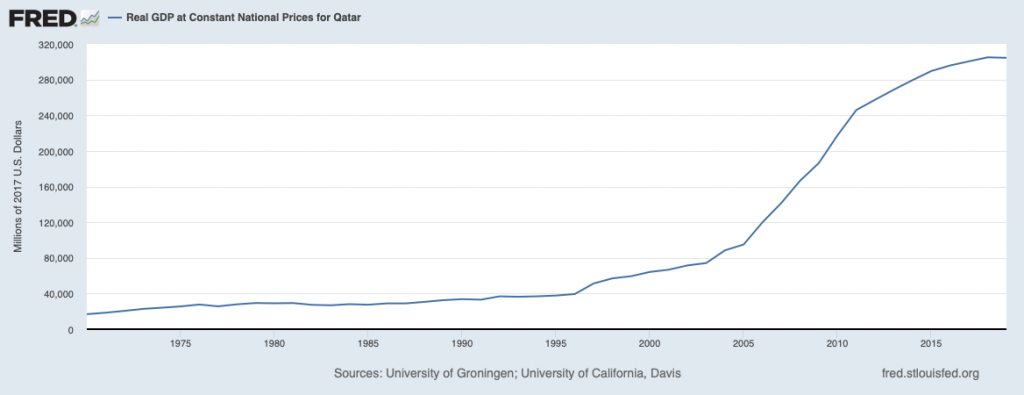

We all know Qatar is very rich; according to World Bank estimates of GDP per capita (PPP 2017$) it ranks 4th in the world. Qatar also got very rich very quickly. Since 1970 its GDP has increased by a factor of 19. The UK’s GDP has increased by a factor of 3 in the same period. This explosion of wealth has resulted in the Qatar we see today; the photos above clearly show the monumental transformation of the country during this time.

Where the economy has grown, so has the number the number of people. In 1995 the population was a little over 400,000 – most of these being Qatari born natives. In 2021, it’s approaching 3 million. However, this isn’t due to a sudden interest in procreation among the Qatari youth; in fact almost all of the population increase is because of inward migration. This reached a peak in 2007 when a staggering 1 million entered the country in a single year – equivalent to 83% of the population at the time. Migrants now make up an estimated four-fifths of the population. But, how can a country maintain a sense of identity for its native citizens with such a huge influx of foreigners? The answer is by ruthlessly excluding migrants from the same rights as native born Qataris: segregating them socially, politically, and economically. This is a win-win for the Qatari state. It can build a new, modern and beautiful country using the oil revenue now flowing into its coffers without a supply of labor, and at the same time maintain its identity and culture – one which they wish to keep distinct from the mostly Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani migrant workers.

At the heart of this policy is the kafala system. This is a system which gives the employers of migrant workers effective control of the legal status of the worker. In practise this often results in workers facing threat of imprisonment or deportation if they leave their job. It also means they must request permission to change jobs – often requiring an intense navigation through bureaucratic systems not known to the worker. According to Amnesty International the kafala system is “inherently abusive” and, in cases, amounts to a form of modern slavery.

All in all, this has resulted in Qatar becoming not only one of the most unequal countries in the world today, but also historically one of the most unequal societies in recorded history. Figure 3 shows the top 10% of earners in Qatar earn 32 times as much as the bottom 50%. This is double the income inequality of the Unites States, which has double the income inequality of Europe. And I’m just talking about income. Notoriously wealth is hard to measure, and no doubt the Qatari elite have assets which are not accurately recorded, but from data available it also ranks extremely high on wealth inequality.

Qatar, even when placed in an historical context, holds its own as a deeply unequal society. For instance, included in its company are the former slave and colonial societies of Haiti in 1780, and Algeria in 1930. Figure 4 (7.3 in Piketty’s book) below shows how the Middle East ranks against these societies (Qatar has is shown to be slightly above the Middle East average in Figure 1). Haiti in 1780 was the archetypal slave colony and one of the most unequal economically in history: the top 10% earned 80% of the income. In terms of income distribution, Qatar is closer to Haiti in 1780 than Europe in 2018. It sits somewhere in the middle between the height of colonial European high-society in 1910 and apartheid South Africa in 1950. Let that sink in.

I don’t intend to equate the plight of migrants in Qatar and slaves in the New World directly. For one, the proponents of the global slave trade, a conglomeration of Portuguese, American, Dutch, Danish-Norwegians, French, and British state sponsored merchants, who forcibly removed peoples from their homes and transported them across oceans against their will. Migrant workers in Qatar have come to the country largely by themselves, are paid wages, and do not face working environment compatible to a plantation. Nonetheless, with reports of wages as low as 45p an hour, migrant labour can hardly be considered fair, or even legal. Moreover, when you begin to think of a new country suddenly endowed or discovered with a large amount of natural resources, but not much labour to employ, it does lend itself to historical comparisons. The Southern Unites States comes to mind.

In short, I hope to have shown how unequal Qatar is and place that in an historical context using the great data available in Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Ideology. The migrant workers in Qatar didn’t just come to build a few World Cup stadiums like the Qatar government would like you to believe (Figure 2 actually shows the net inflow of migrants has actually been declining since Qatar won the bid). Migrant workers have been used to build absolutely everything you see in Qatar, from the airports, metros and shopping malls to the skyscrapers and hotels – none of which they own or even receive a minute slice of the income which they generate. In return they have been denied the rights and privileges of the standard of living which they made possible. In the World Cup contruction many have also lost their lives – 6500 according to Guardian research or 400-500 which was flippantly admitted by a Qatari official on Piers Morgans’s YouTube Chanel.

Of course, the economic inequality of workers and residents of Qatar is only one perspective to take. Not least the absence of rights for LGBTQ+ people also speaks to the deep social inequalities in the country. These are all issues worth highlighting. Perhaps the legacy of this World Cup will be the power of the international spotlight and its influence on future reform. Although somehow, I think not.