The UK has a fairly good education system by international standards. We rank eighth out of forty-one similar countries for educational attainment, and we have a secondary school graduation rate above the OECD average (OECD,PISA). However, the divide in outcomes between private and state school pupils has grown rapidly in the last decade, and the difference in funding between state school pupils and private school pupils has reached record levels. Pressures on education resources- exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic – alongside falling teacher numbers, due to stress and burnout, are a fundamental risk to social mobility and meritocracy in the UK.

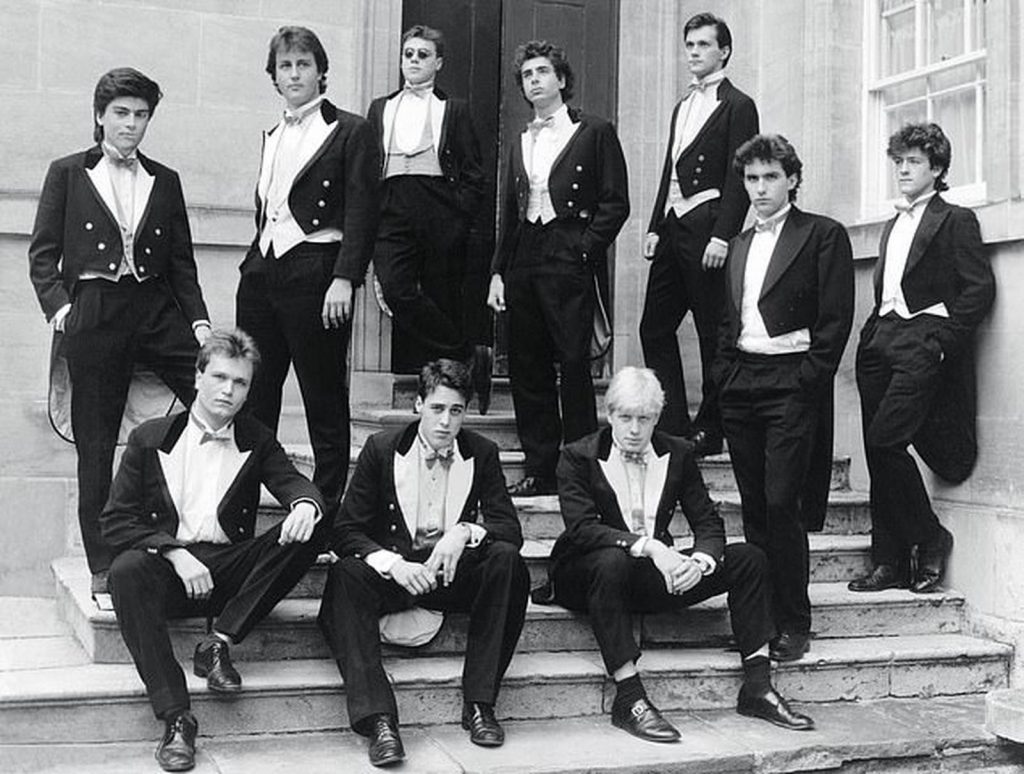

For context, education in the UK is highly stratified; the three main systems are state, grammar, and private. The vast majority of students are enrolled in publicly funded state schools. A few local authorities also have a grammar school system; grammar schools aim to promote social mobility through a selective admission process at aged eleven. However, the evidence that selective education improves social mobility is very weak, and the system is hardly meritocratic when wealthy households can afford to pay professional tutors for the entrance exams. Thirdly, we have the private school system – open to high-income households which can afford the average annual fees of £14,940 for a non-boarding day school. Private boardings schools (confusingly named public schools ) include famous schools like Eton, where average fees increase to a staggering £35,289. When you consider the average household disposable income in the UK is £32,300, very few people can afford these institutions (IFS, ONS).

The gap in student outcomes across several measures between state school and private school pupils is huge and growing. Evidence from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), which published a report last year on private schools and inequality, suggests that not only do privately educated pupils do better at school (when compared with state school pupils of similar cognitive ability, family background, and income), but they also receive an earnings premium well into their careers. The IFS finds the earnings premium, by the age of 42, can be as much as 35% for men, and 21% for women. A significant proportion of this can be explained by occupational choice. Thus, why is it that less state school pupils enter high-earning industries like law and finance? Is it due to a lack of social capital, less parental pressure, or low confidence and knowledge about these sectors? The answers to these questions are not clear, but future research should investigate what is determining those choices. Analysis of the proportion of privately educated students in elite occupations highlights the large disparity in outcomes. For example, 51% of Junior Ministers, 42% of media columnists, and 59% of Permanent Secretaries – the highest position in the Civil Service- went to a private school (I can’t find data on banking, finance, or law but the pattern is clear). This compares to 18% of pupils between the age of 16-19 who attend private school, or 6.4% of all pupils.

Clearly, attending private school offers a range of potential advantages – not least in terms of the educational resources. However, research also suggests that private schools deepen an individuals social capital. The impact of social capital on student outcomes is very hard to measure, but it likely explains a non-trivial amount of the private earnings premium when combined with a better resourced education, and higher selection into top-earning professional industries.

One may argue that private schools offer several social benefits. For instance, 56% of private schools are registered as charities and therefore should legally be providing a ‘public benefit’. Charity status can be met through providing means-tested bursaries, partnerships with local state schools, and encouraging charitable work among pupils. The evidence of a wider social benefit to private schools is not conclusive, but it most likely won’t be enough to counter-balance the social costs of the private and state resource divide. Moreover, bursaries are rarely enough to cover the expenses of many private schools, and partnerships with state schools have nose-dived since the pandemic.

Nonetheless, a radical policy to abolish private education has about an equal chance of passing through parliament as Matt Hancock does of hosting a prime-time Saturday night television show (although I wouldn’t put it past him). But, I believe significant reform which narrows the outcome gap between state and private school pupils would deliver substantial social benefits. As I mentioned in the opening paragraph, it’s not as if the UK doesn’t have a good education system; I would argue that we need to fund this system as best we can and ensure it’s fit for standards, regardless of the impact on private schools.

The benefits of a better educated and more aspirational workforce are enormous not just for individual wellbeing but also economic growth. Economists are often in disagreement about the factors explaining economic growth, but few argue that human capital (skills, education, training) are not fundamental drivers of long-run productivity (which has been dismal for over a decade in the UK). Moreover, low productivity growth, coupled with the worst (excluding the US) income inequality in the western world, has substantially harmed the UK’s ability to weather the shocks of Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine. A better funded and larger state education system which produces a well-trained workforce with more skills, would not only help reduce long-run inequality, but also drive long-run productivity.

“The average fee for a boarding school is £32,000, a VAT charge of 20% on top of that is £6,400. The state spends an average of £6,125 per pupil. Effectively this means the UK taxpayer is subsiding the education of the richest families children to go to elite boarding schools for the same amount as their own children receive in education funding.”

A low-hanging fruit policy proposed by Labour is to end the charitable status given to private schools, and in turn end their exemption from VAT and business tax rates. This isn’t just a leftist view. This exact idea was proposed previously by Micheal Gove, Tory education secretary for four years between 2010-14, who wrote in 2017 about the unfairness of the VAT exemption on private schools. A simple back of the envelope calculation reveals the clear injustice of the VAT exemption. The average fee for a boarding school is £32,000, a VAT charge of 20% on top of that is £6,400. The state spends an average of £6,125 per pupil. Effectively this means the UK taxpayer is subsiding the education of the richest families to go to elite boarding schools for the same amount as their own children receive in education funding.

Last month, within the Labour Party, the motion to set up a new committee to investigate private schools’ “charitable status” failed by 303 to 197. Critics argue the impact of the policy is unclear, and by increasing the fees of private schools it will hurt aspirational families and force them to take their children out of private education. Some families would indeed be priced out of the private market, and others would need to reconsider the benefits of private education at the higher fees. However, the exact reduction in the size of the private sector depends on how many families would decide to switch to state school provision. Given fees have been increasing steadily for years, it seems unlikely many families will be perturbed by an increase in price. Furthermore, conservative arguments about free-markets are strangely absent in this domain – why exactly should governments intervene to influence the market price of education? You tell me. A larger state sector accommodating a more diverse range of students would also create a range of positive peer-effects between pupils, and be accompanied with an increase in tax revenue of £1.7bn a year to spend on teachers and classroom resources. In comparison to the school budget of £57.3bn this isn’t huge, but its an improvement with essentially zero-cost on 94% of children in the country.

Overall, the private and state school divide has a huge impact on the outcomes of pupils. This divide has been growing since 2010, has been made worse by the pandemic, but it can also be helped by effective policy choices – in particular scrapping the charity status of private schools. This isn’t a question of whether you believe private education is morally wrong or right, nor whether you think people should have the choice. Politicians on the right will focus on the freedom to choose, however, your ability to choose depends on your income, and it’s simply unfair to provide tax-breaks which slightly reduce the economic burden for rich families (again so much for the free-market eh?). Moreover, an unequal society- with poor social mobility -harms everyones incomes because it creates a less dynamic and prosperous economy. Hence, a more equal education system would feed itself into a better economy, where if you choose to pay for education out-of-pocket then fine, but if you don’t, then you can at least know the state system is adequately funded.

What ranking does the UK hold among similar countries for educational attainment? Regard Administrasi Bisnis