The idea of a tax on individual wealth has been around for decades, and every so often it creeps into the mainstream. However, as the energy crisis has highlighted the excess profits of energy companies and the disastrous “Kami-Kwasi” budget has left the UK government scrambling to balance the books, the wealth tax has gained real momentum. I focus on two things: (1) how much support does a wealth tax have politically and publicly in the UK? And (2) could a wealth tax be a silver bullet for the fiscal “black hole”?

Firstly, before answering these questions, it’s useful to know exactly what people mean by a wealth tax. A wealth tax is a broad base tax on all forms of financial wealth. Its proponents argue it could be levied as a one-off tax or at regular intervals, and apply to either individuals or household units. Policy makers can decide on the wealth thresholds to use. For example, supporters argue a wealth tax could apply to wealth greater than £500,000, or perhaps £1m, or even £10m. Some also argue that primary homes should be exempt. For instance, if someone owned (without any mortgages) two properties worth £1m, but lived in one of them, then a 1% wealth tax would leave that individual liable to pay £10,000 on the £1m of wealth held in a second-home (assuming that they don’t own any bonds, stocks, or other financial assets). The critical point is that a true wealth tax applies to all wealth, so for a good introduction to what is wealth, see this video from former city trader Gary Stevenson, who has recently been putting out some excellent stuff on the UK economy.

Turning back to the question of political feasibility, Rishi Sunak was asked at PMQs (26th Oct) whether he would introduce a tax on wealth. As he has done on many occasions when asked about the topic, he dismissed the question and gave a generic answer about fairness. Also, although the question came from a Labour MP, the top of both major parties are in agreement on this issue; Kier Starmer has rejected the idea of introducing a wealth tax if he came to power. For now, it seems senior politicians view a wealth tax as a non-starter.

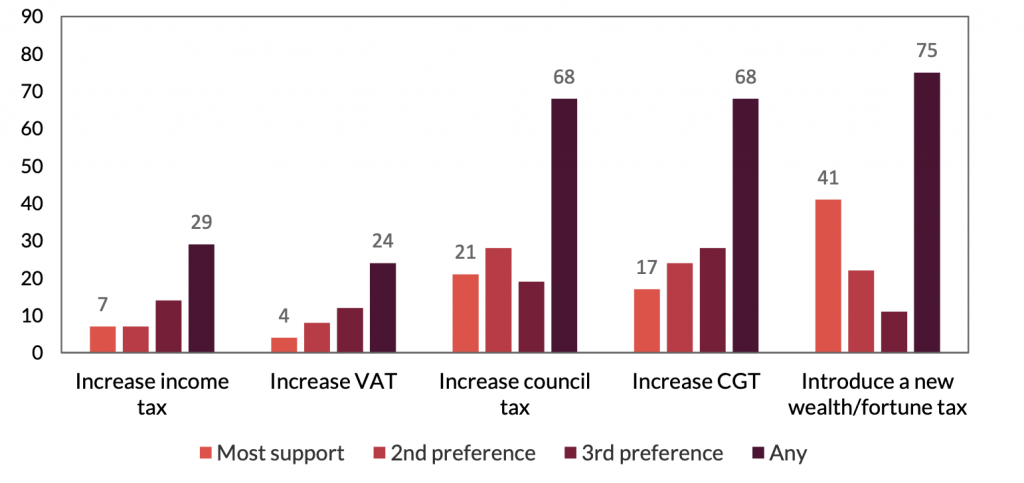

But what about the public – what do they think of wealth taxes? After all, on some level, politicians should reflect the average view of the British population. The Wealth Tax Commission conducted the first UK empirical study on public support for wealth taxes in 2020. They found that 75% of respondents supported a new tax on wealth, with 41% putting it as their most preferred option. Surprisingly, they also found that people on incomes below £20,000 were less supportive of wealth taxes – perhaps pointing to a lack of understanding on who would actually have to pay. Nonetheless, the report concludes that wealth taxes do have broad based support in the UK. However, YouGov polls appear to suggest that many view wealth taxes as a less fair way of taxing: 59% of people think income taxes are fairer than wealth taxes. The wording of this question isn’t great, since wealth taxes can work alongside income taxes to deliver a fairer system overall – rather than being a substitute for each other. Yet, this does imply that people feel somewhat more attached to the wealth they have accumulated than the income they have earned.

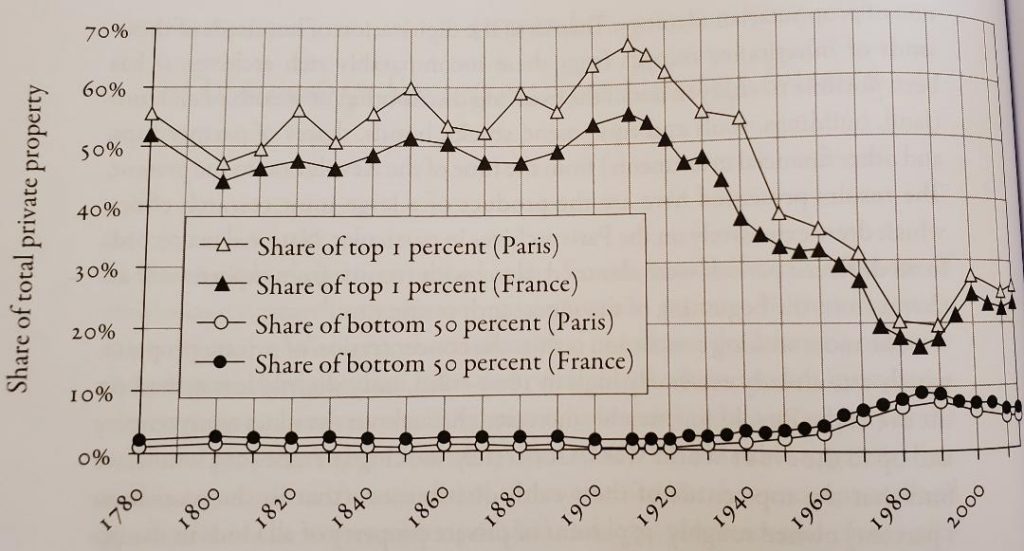

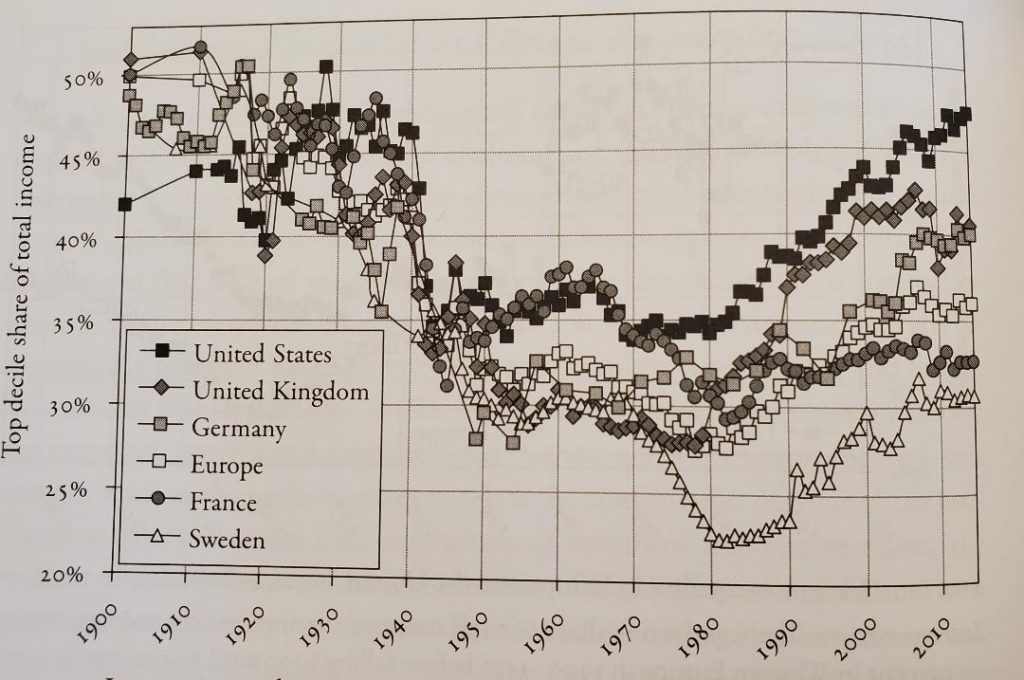

So, if the public in general are not opposed to wealth taxes, and they agree that the gap between the rich and poor is too wide, what accounts for the lack of political will to push wealth taxes? One explanation is the ideology of ownership at the top of British politics, and generally within the establishment as a whole. In a previous blog, I wrote about how Thomas Picketty, an academic economist who has proposed a global wealth tax, describes the current ideology of our time as “neo-proprietarian” – a belief that private property is sacrosanct. This ideology justifies inequality on the basis that wealth has been accumulated by individuals due to their own merits, thus ownership of that wealth shouldn’t be taxed.

A secondary factor at play could be the intergenerational transfer of wealth implicit in a wealth tax. It’s a statistical fact, and also obvious in everyday life, that most wealth is held by older generations usually over the age of 50. Although not surprising, since older people have been here longer, and therefore have had more time to accumulate assets, it is not so obvious that this is fair. For instance, older generations were able to get on the housing ladder much easier, they also had access to free university education, as well as lived during a time of exceptional economic growth. Yet, since older generations are more represented in politics and more likely to vote this could greatly reduce the probability of any political will to impose taxes on wealth.

How much would a wealth tax raise: silver bullet or not?

On the latter question of how effective a wealth tax could be, The Wealth Tax Commission assesses that a one-off wealth tax levied on wealth above £500,000 at a rate of 5% would raise £262bn. To put that in perspective it would fund the NHS for almost 2 years. If an annual wealth tax could raise that kind of revenue on a regular basis, the gains are potentially huge. However, the commission concludes that the administrative costs of an annual wealth tax would be too onerous, therefore they support a one-off wealth tax over a regular one.

Nonetheless, despite the large revenue potential of even a one-off wealth tax, the Commission recommends that reforming the taxes already in place is a 1st best option over the introduction of any new ones. One potential reform is on share buybacks. Share buybacks are when a public company uses profits to buyback its own shares. This entails a significant cash transfer to wealthy shareholders who sell the shares back to the company. Recently, instead of investing profits in say green technology or new products, many companies have simply been shovelling cash back to their owners. Therefore, a tax on this behaviour is an easy way to target this wealth.

The Biden administration has taken action on this already. They have just passed an exercise tax on share buyback schemes, which will come into effect at the beginning of 2023. The IPPR, a think-tank in the UK, has also recently published analysis which estimates a similar scheme in the UK could raise £225m a year, with a higher emergency rate on specific energy companies raising £4.8bn. Alongside a buyback tax, simply raising the tax on dividends to the same level as income taxes could raise £6bn a year. Both of these measures would go a long way to reducing wealth inequality in the UK.

Overall, it looks like a new wealth tax is highly unlikely in the short to medium term, not least because it would require a dramatic change in the ideological principles of private property and wealth. However, the government has options aplenty to make meaningful changes to the current system. Following the US on a buyback tax is an obvious example. Yet, the UK government seems unwilling to implement these changes and the mainstream media doesn’t even present them as options. This is despite there being support from multi-millionaires to make the system fairer, and the evidence presented here on public support for re-distribution. Hopefully, a positive precedent develops from the current (ineffective) windfall taxes on energy companies, but the appetite for bigger leaps forward is clearly lacking.