Introduction

The UK’s exit from the EU, and its desire to look outwards for new and prosperous trading relationships with economies around the world has opened a new realm of possibilities. But, is the grass always greener?

This post is split into three sections. The first collates evidence on future projections of the world economy. This highlights which regions and economies may become prosperous trading partners for the UK in the future. In the second and third sections, I look at what this means for the UK. I explore two important questions that need to be considered if the UK is to benefit from emerging economies: is GDP the key determinant of bilateral trade, or in other words does geography matter? And secondly, do emerging and growing economies demand more imports, and more subtly, is that demand likely to be in sectors which the UK exports?

Section 1: Future trade prospects

One of the key arguments made in the debates around Brexit was that the UK will be free to agree its own bilateral free trade agreements around the world. This would allow UK businesses to gain access to rapidly growing emerging economies and increase the UK’s presence in the global economy. This idea has been pushed by senior conservative MPs, with the often quoted IMF statement of “90% of global economic growth will occur outside of Europe in the next 10 to 15 years”.[1] The theory behind this argument is that emerging economies will offer far more opportunities that the stagnating European economies. Hence, the UK, acting under its own dynamic trade policy will be in an ideal position to reap any rewards. Furthermore, the UK’s expertise in services will be in huge demand as emerging economies transition away from manufacturing to a services-based economy.

One of the key assumptions behind this theory is that geography doesn’t matter for global trade. If emerging economies are growing then the UK should be able to tap into this growth, ideally through signing a free-trade agreement or through other less formal instruments for promoting trade.

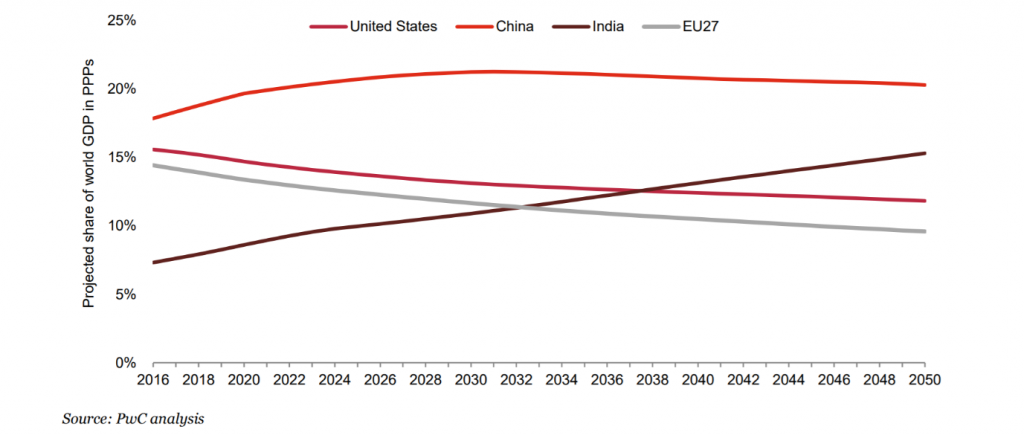

Figure 1 shows one example of a modeled projection of the global economy. According to this model, the EU27 share of global GDP (PPP) will fall from roughly 15% to less than 10% over the next 30 years.[2] This coincides with a dramatic rise in India’s share of global output. The US also must give way to India, as China solidifies and maintains a dominant position in the global economy.

Figure 1 – projected share of global GDP for four of the world’s key economies

This projection is shared by other analytical papers, for instance, HSBC project that emerging market growth will be 4.4% between 2018-2030 compared to just 1.5% for developed markets in the same period. Accordingly, their estimates predict that over the coming decade 70% of global growth will be from countries currently described as emerging (a little less than the 90% IMF forecast but still a considerable amount).[3]

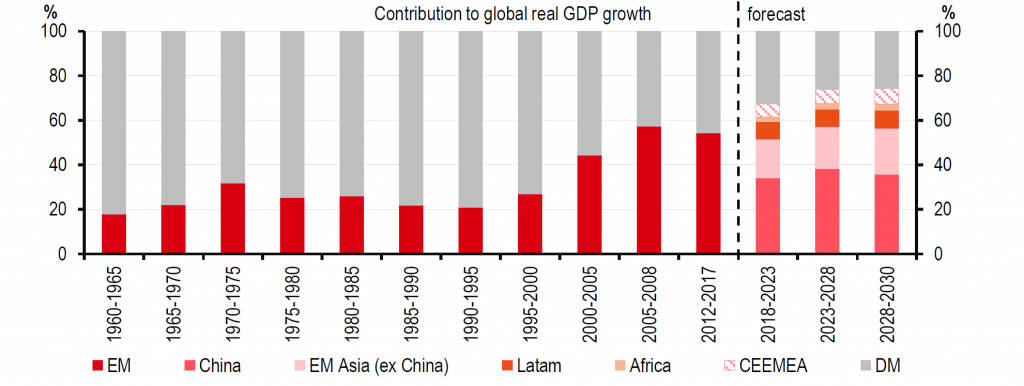

Figure 2 shows how global growth is predicted to be proportioned out according to the HSBC model. In predicts that China will contribute the most compared to other economies. Emerging markets in Asia (excluding China) are predicted to account for roughly 20% of global growth in the next decade. CEEMEA is a description of the EU economies which shows a significantly smaller contribution to global growth, about on par with Latin America, but still more than Africa.

Figure 2 – Proportion of global growth by economic region

Source: HSBC analysis of World Bank data.

Thus, the evidence tells that Europe is experiencing a relative decline in economic power as the emerging of economies of Asia gain more and more ground. Undoubtably, this will present opportunities for UK businesses.

Of course, as with any projection of the future, the estimates are highly susceptible to change. Therefore, these estimates should be taken with a high degree of caution. Nevertheless, they do show a general trend of a shifting economic power base towards Asia. In fact, by 2024 the IMF predicts that emerging Asia will have 38.6% share of global GDP compared to Europe’s 14.6%.[4]

Can we really discount Europe?

Whilst the decline of Europe relative to other global economies seems to be a key trend for the next decade and beyond, this does not necessarily mean that advanced economies within the European bloc will cease to have active and flourishing economies, with substantial demand for goods and services. For example, PwC’s model, which showed the rapid rise of India and decline of Europe, also predicts that in 2030, three (excluding the UK) of the top 15 global economies will remain in Europe, the same figure as in 2016.[5] Total UK trade with these countries was 41%[6] of total EU-UK trade in 2018 and 20% of overall UK trade – the same proportion as the US and ten times as much as India. Thus, advanced economies within Europe will, in all likelihood, remain key trading partners regardless of tectonic shifts in economic power towards the east.

Section 2: Are we living in a post-geography trading world?

On the 29th September 2016, the then Secretary of State for International Trade, Liam Fox, proclaimed that we may now be entering a “post-geography trading world”.[7] In this world the barriers of time and distance matter less as new technology and the importance of digital markets and services begins to dominate physical goods. This view was brought to the foreground more recently, by the PM, Boris Johnson, speaking on the 3rd February 2020 in Greenwich, he explained how the distance between Wales and Beijing was smaller than the distance between New Zealand and Beijing, however, New Zealand trades more with China than Wales does – demanding to the audience “do not talk to me about distance”.[8] However, can we really say geography does not matter, or perhaps more softly, does it matter less now than it used too? And what does that mean for the UK’s future trading relationships with the emerging economies outlined earlier?

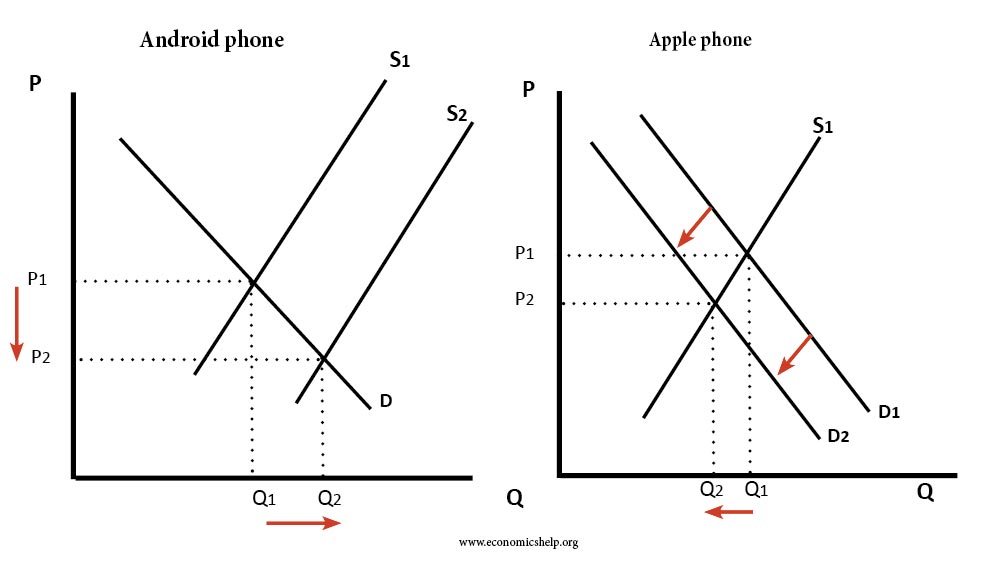

One of the most cited, and widely held, theories in economics is the gravity theory of trade. This states that bilateral trade between two economies is determined by two elements: (a) the relative size of the economies and (b) the distance between the two economies. Hence, we observe in the data, higher trade flows between large economies and higher trade flows between economies which are closer to each other. Figure 3 shows this relationship graphically for the UK economy, with total trade measured on the y-axis and distance from London on the x-axis. A clear negative correlation exists between total trade and distance.

Figure 3 – Total bilateral trade (ONS, 2018) vs Distance from London (km)

Source: Analysis of ONS data 2018

However, proponents of the post-geography trading world downplay the significance of geography in determining trade flows. This undermines the gravity theory of trade outlined above, for which there is a large body of supporting empirical evidence.

Despite the growth of services, digital markets, and technological improvements in transportation and logistics the literature suggests that geography maintains a significant explanatory power on the value of trade between economies. For example, Disdier and Head (2008) conducted a meta-study of 1467 distance effects, estimated in 103 papers published between 1870 and 2001. They find that the distance effect has an estimated mean elasticity of 0.9, meaning that a 10% increase in distance causing a 9% decrease in bilateral trade.[9] They also found that the main difference in estimated distance effects, across their sample of papers, was being caused by the time period of the data used in the estimation. Their results indicated that the distance effect had decreased between 1870 and 1950 and then started to rise. This is contrary to the argument that new technologies are decreasing the importance of distance in global trade.

World Bank economists have also studied how the efficacy of trade agreements are impacted by geography.[10] The find that the effectiveness of economic integration agreements (EIAs) decreases with distance. They show that is effect is mainly being driven by geographically sensitive intermediate goods. Intermediate goods, as opposed to final goods, depend a lot more of localised supply chains, which require timeliness and proximity to work. For example, car manufacturing involves bringing several different intermediate parts together in a short period of time. Therefore, the distances between manufacturers matters hugely. In the case of final goods, they find that EIAs can increase trade regardless of distance. However, the majority of UK trade is in intermediate goods, as is most global trade.[11]

So, it appears that geography is still an important factor in trade. However, even if we assume geography matters less and we accept that emerging economies around the world will account for most of the global growth. Are these necessary and sufficient conditions for increased trade with the UK? To make this step, one must also assume that economic growth in these economies will lead to greater import demand – or, more precisely, higher demand for UK produced goods and services.

Section 3: does higher growth automatically mean more trade?

The UK is an advanced economy, with a highly developed manufacturing industry specializing in a small range of high value goods. It is also predominantly a service-based economy with X% of total output being in services, this is mostly professional business services like accountants, lawyers, bankers, and consultants.

UK businesses can benefit from emerging market growth if these emerging economies start to demand advanced manufactured goods and services from abroad. However, it remains contentious how quickly this will take place or whether it will take place at all. For example, how likely is it that a Chinese business, with little knowledge of UK business culture, or perhaps even the English language, will choose a London- based law firm over a Beijing based-one? Moreover, China has already shown its prowess in developing its own industry leading companies like Huawei, Tencent, and Alibaba which can easily satisfy Chinese domestic demand without turning to foreign imports.[12] India, with its own hugged domestic population, will also be extremely difficult for UK business to penetrate and gain a foothold against domestic firms. These two countries combined are predicted to account for 30% of global output by 2030.

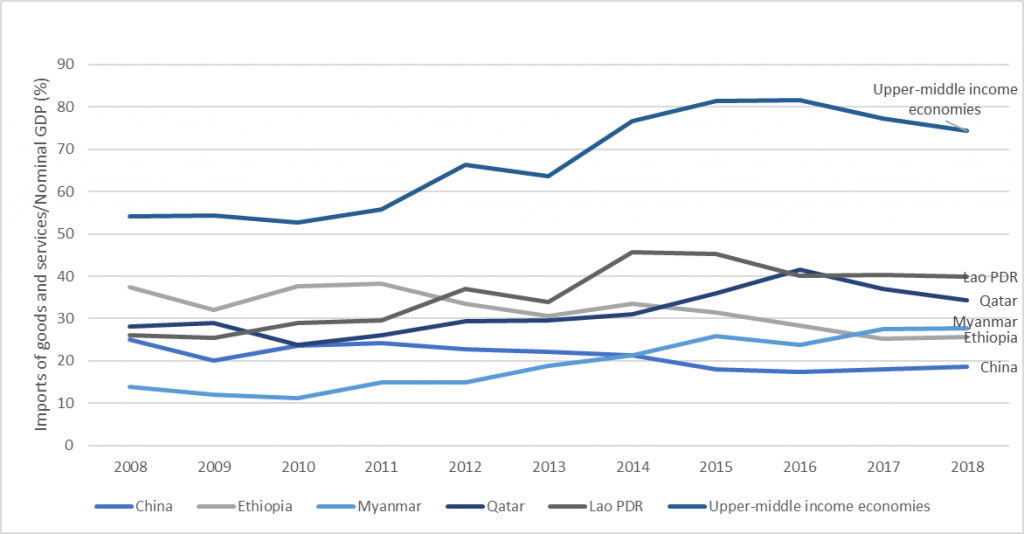

One way to examine this argument in data is too look at which countries have been growing the fastest over the last decade and whether that growth has led to an increase in import demand. Figure 4 shows the top five fastest growing global economies between 2008-2018[13] and imports as a % of GDP in each of those years. The results are mixed. For instance, China’s imports as % of GDP were 25% in 2008 but this had dropped to 19% in 2018. Similarly, Ethiopia’s imports as a % of GDP were 32% in 2008 compared to 25% in 2018. Clearly, import demand relative to the rest of the economy had fallen in these two economies. On the other hand, Qatar, Lao PDR, and Myanmar all saw a sizable increase in imports relative to the rest of the economy. However, looking at all upper- middle income countries the sample size is a lot larger.[14] This shows a significant increase in imports as a % of GDP. In this period, the combined GDP (PPP) of upper-middle countries grew by 89% and imports as a % of GDP increased from 55% to 75%. Therefore, it appears that as economies have been growing their need for imports has also increased, which is promising for the UK trade prospects.

Figure 4 – Imports as a % of GDP for the Top 5 fastest growing countries (2008-2018)

Source: analysis of world bank data

Academic literature on the relationship between trade and economic growth tends to focus on the casual impact of trade on growth not of growth on trade. This limits the usefulness of literature to answer the question of whether fast emerging market growth will lead to increased import demand, however, there is a robust consensus within the literature trade is highly correlated with GDP.[15]

Nonetheless, the composition of import demand from emerging economies will be important. For example, a growing economy such as India may begin to trade more as it develops, but for the UK to benefit the composition of that trade will have to be in goods and services which the UK produces.

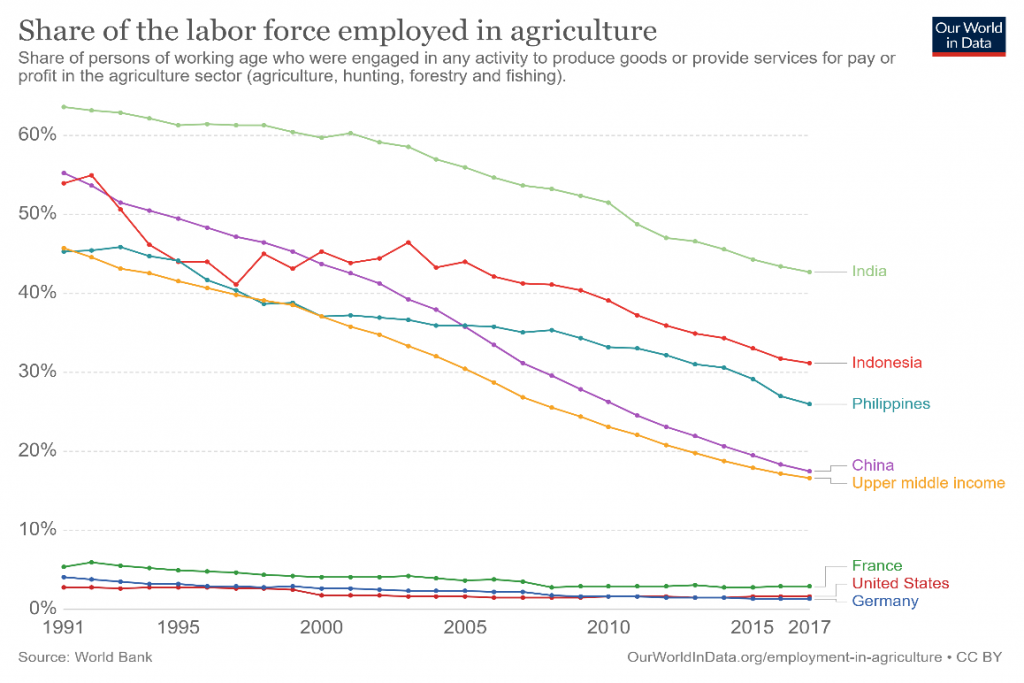

Figure 5: Share of labour force employed in agriculture[16]

Figure 5 shows the share of the labour force employed in agriculture in four of the fastest countries in the world, as well as the upper-middle income countries. India still has over 40% of its labour force in the agricultural sector, with Indonesia hovering at 30%. This is important as the UK mainly produces manufactured goods and professional services for the global economy. Hence, the percentage of the labour force employed in agriculture can be used as a proxy for the countries need for manufactured goods and professional services.[17] Whilst there is a clear trend as these economies have developed in the last thirty years that agriculture has become less important, it also shows how many of the emerging economies expected to account for the majority of global growth in the next decade are still relatively dependent on the agricultural sector. This may limit the extent to which UK can benefit from trade with these countries. For comparison, if you look at the UK’s three current largest trading partners, the share of labour force in agriculture is considerably smaller.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/britains-trading-future

[2] https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:DbH1S197Ye0J:https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/assets/pwc-the-world-in-2050-full-report-feb-2017.pdf+&cd=8&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=uk , p.20

[3] The World in 2030, HSBC, https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:MOsQ4GFG3rgJ:https://enterprise.press/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/HSBC-The-World-in-2030-Report.pdf+&cd=5&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=uk

[4] https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=55&pr.y=6&sy=2017&ey=2024&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=001%2C110%2C163%2C119%2C123%2C998%2C200%2C505%2C511%2C903%2C205%2C400%2C603&s=PPPSH&grp=1&a=1

[5] Ranked by GDP (PPP). These economies are Germany (5th to 7th), France (10th to 11th), and Italy (12th to 15th).

[6] ONS 2018 data of proportion of Germany, France, and Italy total trade within total EU trade.

[7] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/liam-foxs-free-trade-speech

[8] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech-in-greenwich-3-february-2020

[9] https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/download/3699.pdf

[10] https://ideas.repec.org/a/spr/weltar/v155y2019i2d10.1007_s10290-018-0327-3.html

[11] https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/10302

[12] https://money.cnn.com/2018/05/28/news/companies/biggest-brands-ranking-2018-alibaba-tencent/index.html

[13] AAGR for 2008-2018 calculated from world bank data. Naura and Turkmenistan have been excluded from the top five because of a lack of import data.

[14] Upper-middle income countries are defined by the World Bank. This includes China, Brazil, Thailand, Columbia, South Africa. A full list can be found here: https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/upper-middle-income

[15] Frankel and Romer (1999) is the most cited account of the relationship between trade and growth: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.89.3.379

[16] https://ourworldindata.org/employment-in-agriculture

[17] This theory is famously known as the Rostow theory of growth model. More information can be found here on the theories assumptions and implications: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2591077?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents