I’ve recently been interested in the role of culture in the process of economic development. Within the growth literature this is a topic which finds less support than other more conventional explanations for the global differences in development, such as geography or institutions. In part, this is due to the difficulty in defining culture – let alone attempting to measure it statistically. However, recent research points to culture being an important factor in long-run and current income disparities, both between and within nations.

What exactly is culture? Huntington (2000) describes it as follows:

“the values, attitudes, beliefs, orientations, and underlying assumptions prevalent among people in a society.”

Clearly, the values and beliefs of a society are likely to shape its political and economic intuitions, as well as affect the incentives and behaviours of workers and businesses. Hence, culture has been claimed to be an important, if not major factor in explaining differences in income across countries. For instance, take Italy, and the widely known Putnam theory. Italy is a relatively small, homogeneously populated, and well connected country which has been politically unified since 1861. However, any visitor to Italy will notice significant differences in the level prosperity between the North and the South of the country. Why is there such a difference? Putnam argues this about culture – or more technically what he terms “social capital”. Broadly, this captures the degree of trust between citizens. Societies with high social capital cooperate better, are honest and value norms of reciprocity and fairness more. In contrast, low social capital societies work together less, distrust others outside their close connections, and tend to display less self-agency over their lives. This can manifest itself in rent-seeking, corruption, and low investment – all of which can blight development.

But where does social capital come from? Moreover, if trust, openness, and self-agency are growth enhancing norms – how do they manifest? And can, or should, public policy play a role in influencing them? Recent research has attempted to answer some of these questions.

A key piece of research in this area is a paper by Tabellini (2010). In this paper Tabellini argues that historical institutions influence contemporary culture, which then affects economic development. Survey data allows Tabellini to codify cultural straights identified as being supportive to growth; trust, respect, and control. These capture an individuals perception of how much they can trust others, how important teaching respect for others is when raising children, and also to what degree they feel like they have control and influence over their own lives.

Tabellini finds that each of these variables are highly correlated with historical political institutions and literacy rates. For example, people living in a region of Europe, which in 1800 was highly literate and governed by strong political institutions (meaning the ruler was constrained by checks and balances on his or her power), are likely to have higher trust in others today. Higher social capital is then found to lead to higher output per capita, independent of the historical institutions and literacy rates, and after controlling for all other variables likely to influence output today. Thus, it appears culture does matter for development.

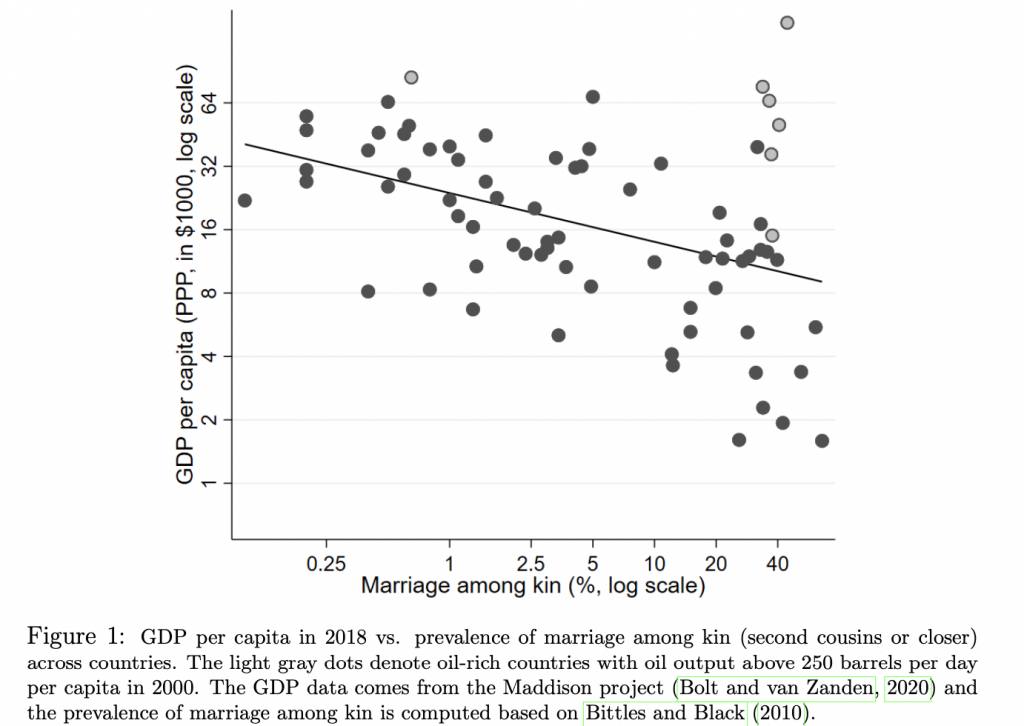

But, how are these “good” norms and beliefs formed? And how are they passed down? In a paper published last month, the role of kinship institutions is argued as being key to understanding this process. The core idea of the paper is summarised in the figure below. It shows a clear negative relationship between the prevalence of marriage between 2nd cousins (or closer) and the level of GDP per capita. The negative slope appears to show that countries with tight kinship cultures tend to be poorer.

In the detail of the paper, the authors construct an indicator of kinship intensity (KII) for each region, which measures the prevalence of norms related to cousin marriage, polygamy, co-residence of extended families, lineage organisation, and community organisation. They find a higher KII to be associated with a lower level of economic development. One of the channels they explore is how the KII impacts trust. They find that tight kins display much lower trust to outside members compared to inside members.

Thus, a story is beginning to emerge: deep-rooted kinship institutions passed down through the generations shape the beliefs, attitudes, and underlying assumptions of the population, which in turn either leads to a positive build up of social capital and sustained economic growth, or incubates norms and ideas that inhibit growth. This is only one story; there are infinitely many more.

However, how does policy fit into this? Is it ethical to even discuss attempting to dismantle certain cultural practises, let only implement policies to do so?

Firstly, it remains an open question as to whether culture, in the sense we have been discussing here, can be influenced by policy. However, a recent paper by Natalia Bou studies the cultural practises of matrilocality and patrilocality (whether male or female children live with the parents are marriage). Bou focuses on specific policy changes in Indonesia and Ghana, which introduced pension systems in 1977 and 1922, respectively. In theory, the practise of having a child live with the parent after marriage is a form pension security for the parents, since live-in children will be expected to provide support and care for the parents. However, the introduction of a pension system has the possibility of weakening the need for this informal system, therefore the policy has the potential to change cultural norms. Bou finds this is indeed the case: males from traditionally patrilocal ethnic groups exposed to the pension policy are less likely to practise patrilocality in the future. Thus, there appears to be some evidence of policy being able to influence cultural norms, but is this an over-reach by policy makers?

The very idea of a discussion around culture may offend some. The notion of comparing one culture to another, and therefore inevitably drawing a distinction between a “better” or “worse” culture, is not one I wish to do. Nor is the idea of a world dominated by a single culture (whether it be predisposed to generate wealth or not) a welcome thought. The beauty of the world is largely derived from its diversity and uniqueness. However, on the basis of growing evidence, cultural norms and beliefs do tend to matter for prosperity. Therefore, by caring about the prosperity and opportunities of others, we must also try to understand what factors hold them back – even when that requires examining culture.

Life is better than death. Health is better than sickness. Liberty is better than slavery. Prosperity is better than poverty. Education is better than ignorance. Justice is better than injustice.

Executive Board of the American Anthropological Associations, 1947

Hence, I argue that the American Anthropological Associations alternative assertion to the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, which they refused to endorse on the grounds of being an ethnocentric document, is a great benchmark to start an examination. Almost all would agree that any aspiring culture would not resist change and progress along those lines. Accordingly, it’s important for economists, anthropologists, and policy makers to continue studying the role of culture in economic development.